159. Watercolor: Glazing vs. Mixing

In the past couple of months, I’ve received some questions about how to layer watercolor. There are lots of resources about glazing (layering) watercolor, but I thought I would offer my two cents!

What is Glazing?

Glazing means layering, but there’s so much more to it than slapping paint on top of paint. But for now, let’s get the basic difference out of the way:

Glazing: building the depth of a painting by layering diluted watercolor, letting the layers dry between applications.

Mixing: combining different wet pigments before applying to the paper.

Why Glazing?

Glazing is a useful technique when building detail, and is less time-sensitive than working wet into wet so it’s especially great for beginners. In addition, it can result in some interesting visual results which I’ll show you in a moment. Layering color this way is essentially color mixing, in a very unique way.

This means you must be aware of which pigments you’re using and whether they play nicely.

You might think, ah that’s easy! If I layer blue over red, I get purple! Well...yes sometimes. But depending on the exact hue of your red or blue, you might be shocked to see grey or brown appear.

Some reds lean more towards yellow and we call them warm reds, while others lean more towards blue and we call them cool reds.

Similarly, some blues learn more towards red, some lean more towards green, etc. You get the idea..

So if you layer a warm red over a greenish-blue, guess what: You just layered complimentary colors, which is a direct path towards neutralising your color and this is why it might look more grey or brown instead of the beautiful purple you were expecting.

Getting to know your paint is crucial in achieving a successful glaze.

Before jumping into the glazing chart, I feel compelled to talk about drying shift, because it plays such an important role in glazing.

What is “Drying Shift?”

Some mediums, especially watercolor, experience what is known as a drying shift. This means that when the paint shifts from wet to dry, it loses saturation and lightens in value.

Some pigments are more drastic than others, so it’s worth doing a swatch sheet to see how the colors on your palette look when they dry.

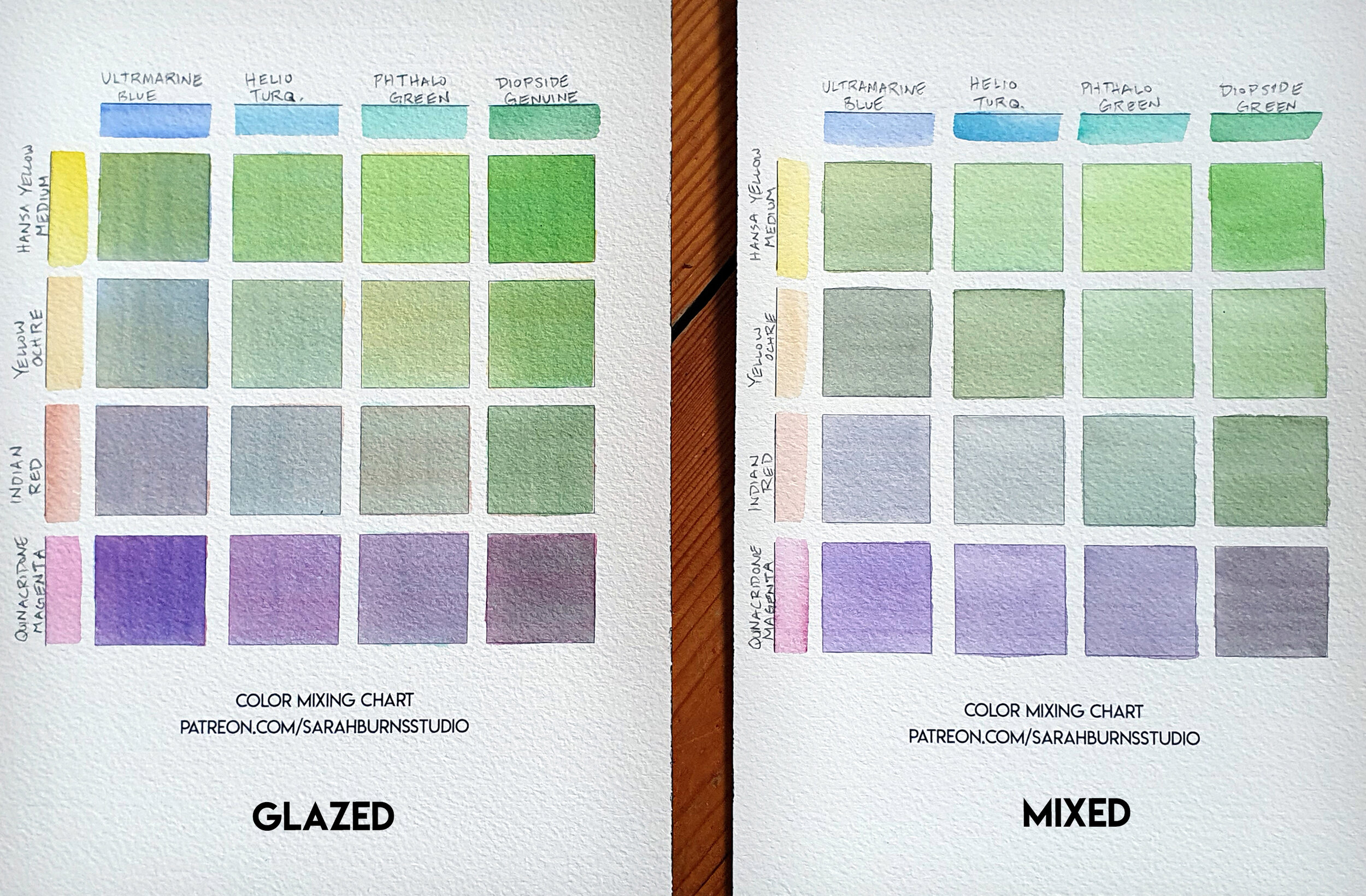

So is the difference between mixed color and glazed color truly noticeable?

YES.

Let’s so a quick comparison. I made a free printable chart for you guys that you can print on watercolor paper and try it for yourself. Or feel free to use it as a guide to draw a similar chart on your paper.

Any time I get a new color, or just need a refresher on how my pigments play together, I make a new chart because it’s so important to be intimately familiar with your pigments.

This is the only way you’ll know what colors you can glaze.

This is what my chart setup looks like:

To start off, choose 8 watercolors that you want to glaze.

For this exercise I will choose two yellows, two reds, two blues and two greens.

It’s up to you to decide how to organise them, but I prefer to group the yellows and reds on one side, and the blues and greens on the other.

When selecting colors, pay attention to their transparency rating. Some pigments are more opaque, and generally they aren’t very good for glazing, unless they go down onto the paper first. One of my colors, Indian Red, is very opaque, so I always make sure to lay it down first.

How to Make a Glazing Chart

Otherwise, I like to put the color with the lightest inherent value down first, and usually that is my yellow.

Work with diluted pigment, not heavy layers. You can layer multiple times if you want, but ideally each layer will be very watered down in order to allow more light to pass through and reflect both colors. This is where water control comes in, so this is a great way to practice. To me this is the trickiest bit. But just do your best.

Try to use the same amount of paint to water ratio for each square, so you get a fair comparison. There’s no perfect science to it, and I just end up eyeballing it until each box looks the same. Fill in each column with the appropriate color.

Let it dry completely.

Only when it is completely bone dry should we start to glaze.

A couple of tips here…

Avoid over brushing with the glaze. The more times you run that brush over the first color, the more likely you could disturb it and end up physically mixing them. Even though that first layer is dry, not all pigments are 100% permanent and they could potentially lift off the paper.

So use confident smooth brush strokes. I like to use brushes with very soft bristles, as this has less of a chance of disturbing the first layer.

And of course, make sure your paint is diluted with enough water so that you can see both colors. This is definitely tricky and takes practice. And remember the whole drying shift thing? Your paint will dry lighter so that is an even further level of complexity. Just do your best, and don’t feel bad if you have to make more than one chart with different amounts of water. I made my chart a bit lighter to emphasize the fact that you only need a tiny amount of color in each layer to achieve a good mix.

I find that when I layer granulating colors, it almost has a duo-tone effect when it’s dry. This can add such a gorgeous effect to your landscapes so it’s good to know which mixes will do that.

Whether or not the glazing technique results in more luminous paintings is a matter of opinion, and also semantics by the way. Now obviously, my mixes aren’t a perfect match to my glazing chart, but it just goes to show you that during a normal painting session, using layers to achieve a certain look is possible. Ignoring the difference in actual hue, I can see a visual difference in my glazes, they almost jump off the page at me, whereas my mixed chart feels a bit more flat.

Even in this quick experiment I see a clear difference and I personally love how glazing looks!