150. Pruning my Watercolor palette to be more Earth friendly (Part 1)

I’m so excited to be writing this post, because this is something I’ve been thinking about doing for over a year! I’m not sure why, but last week it suddenly hit me that IT’S TIME!

What do you mean, Earth Friendly?

A lot of pigments contain heavy metals such as cobalt, cadmium, aluminum, and nickel. So every time you wash your brushes and palette in the sink, or dump out your used paint water, that enters our water system. Depending on where you live and which drain you use, that water may not be treated before it’s released into the environment.

If these elements end up leaching into crops, wells, and oceans, it moves up the food chain and comes back to bite us (and our animal friends!)

Every single choice we make at home accumulates across humanity and impacts the world.

I choose to make my painting process more earth friendly, because I care, and it’s really not that difficult.

THE GREAT WATERCOLOR PURGE OF 2020

As I began this journey, the more I research my paints, the more overwhelmed I got. I want to share my process for learning about my pigments, how I make my decisions, and what the final results are! Hopefully this will help someone who is also on this journey.

(FYI - I did not throw away any paint. All paints that I removed from my palette are stored and saved to be used for future teaching workshops. You can give paint away, or sell it, or store it for an apocalypse)

How to get started

For this to even be possible, there are a few basics that need to be explained.

Pigment name & numbers

Every single tube of paint contains at least one pigment. Every single pigment has a number to designate what it’s made with. See Exhibit A.

Every brand has it’s own version of each color, so even if they use the same pigment, it could look and act very differently.

The way Brands name their colors can be misleading. ALWAYS look at the pigment number when doing research, not the marketing name (the name they put on the tube).

Exhibit A. Source: handprint.com

onto the fun stuff!

And by fun, I mean the part where I spent 3 nights in a row writing down all my pigment numbers, researching what exactly is in each pigment, as well as looking at their lightfast ratings (how much they fade in sunlight over time) and opacity (I prefer transparent colors).

It takes time and patience. And coffee.

My four biggest sources of information:

Dr Oto Kano’s “Colossal Color Showdown” (and literally everything else she does)

The Process

Here’s the approach I took:

Step 1

Identify all of your pigment numbers by reading your labels (or using the Brand’s website if necessary), as well as their lightfast ratings, and opacity (and whatever else matters to you). Start a spreadsheet or paper list. (I prefer sheets of paper that I can carry around and throw in the air in moments of frustration).

Step 2

Eliminate all colors that contain heavy metals. I focused on cobalt, cadmium, aluminum, and nickels. Let me tell you… this step is PAINFUL. I was almost in tears as I pulled out several of my most-used, favorite colors. Some colors that I’ve used in almost every single painting I’ve made since 2016!

But you have to be cutthroat. Strict. Don’t chicken out or say “it’s just one tube…”

No. Go all-in.

The good news is that because of modern technology we have amazing synthetic pigments or “hues” that mimic cadmiums and the like, which are safe alternatives.

Trust me, after you do this, it’s like a breath of fresh air. I felt so good when I finally let go.

Step 3

Immediately eliminate any color with a poor lightfast rating. These are considered fugitive colors. All colors will fade overtime, especially in sunlight. Some take hundreds of years. Others take months. This is especially important if you sell your artwork.

The most fugitive colors are*:

PY40 (Aureolin)

PY117 (azomethine copper complex)

PR48 (beta oxynaphtholic acid scarlet or “scarlet lake”)

PR83 (alizarin crimson)

PR170 (Naphthol red, depends on Brand)

PR216 (pyranthrone red deep or “Brown Madder”)

PR60 (disazo lake)

NR9 (Genuine rose madder)

PR88 (Thioindigo violet)

PG8 (nitroso iron complex or “hooker's green”)

PV39 (triphenylmethane violet)

These will fade within weeks or months.

*Of course, there are other pigments that have less than ideal lightfast ratings, so research is needed for all purchases.

Step 4

Decide whether you want to keep opaque colors or transparent colors.

Why doesn’t this matter?

Opaque colors make glazing more difficult. Glazing is an important part of my process, and you need to decide if that is true for yourself.

Step 5

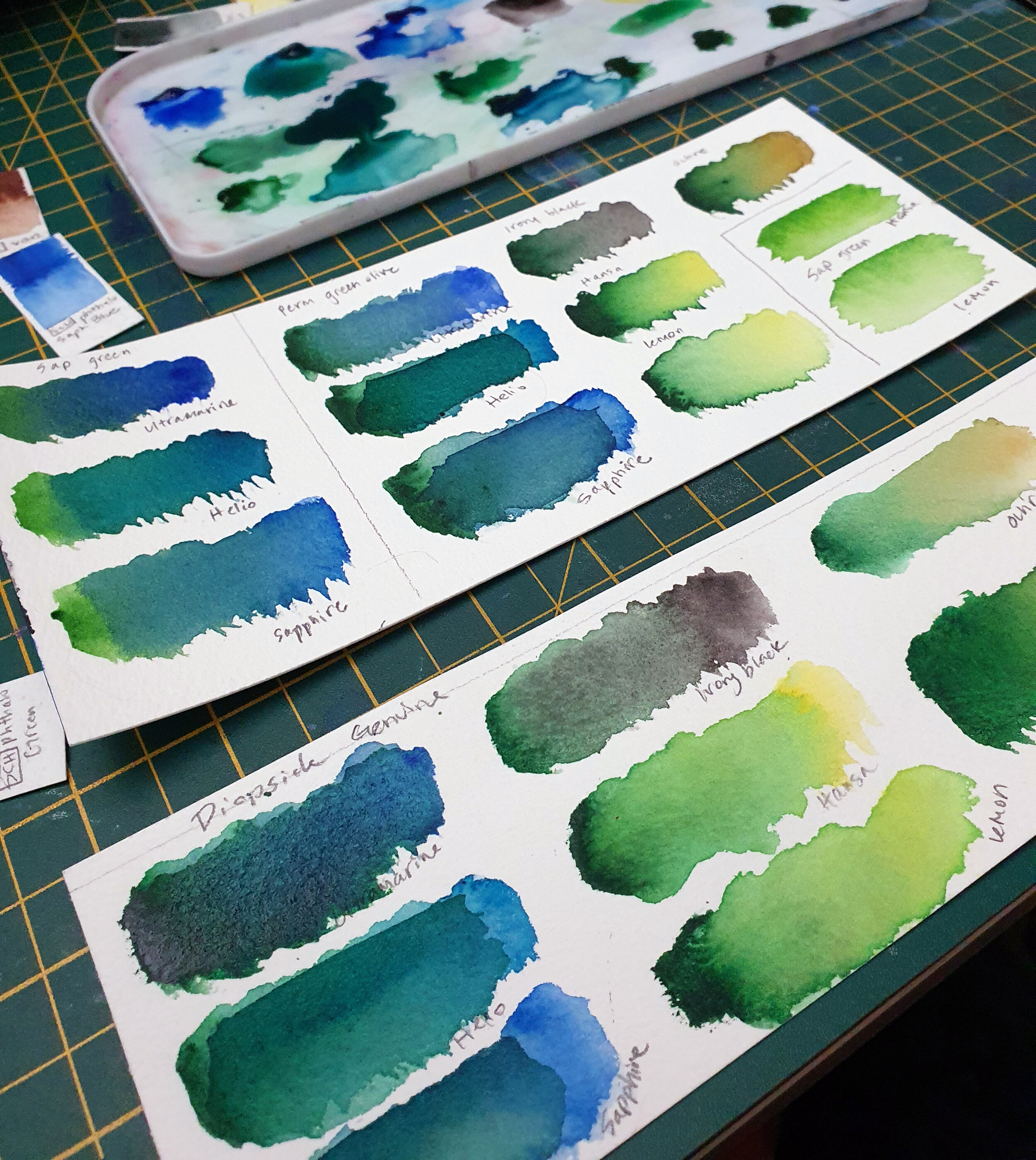

Make color swatches of all remaining colors. Look at them in natural light. Artificial light. Closely observe how they behave while swatching.

Basically, get to know your colors. If you are like me, you’ve been using some of the same colors for years, so you already know how each one behaves.

So perhaps this step becomes more intuitive. A gut reaction. Write down your thoughts about each one.

Step 6

Time to eliminate duplicates and prune down to your desired number of paint.

How do you decide? It’s easy for me. My favorite palette contains 18 wells for paint. I want 18 colors or less.

Know your intention!

It’s very important to know why you are doing this and what you need as an artist.

I mix most of my colors from primaries, usually sticking with 3-5 colors per painting. Sometimes it’s nice to have a bunch of convenience mixtures but a lot of times they just get in my way. A “convenience color” is like green or purple. You can mix primaries to make them, or you can just buy a tube of premixed color. How convenient!

So my desired outcome is to have 18 (or less) colors that I LOVE and let those live permanently on my palette.

I started this process with 56 colors. I ended up with 14.

I accumulated a lot of colors since 2016 as I learned what I needed. But since 2018 I’ve stuck very much to a primary palette across all my paints (oil, acrylic, etc) and only reach for convenience colors once in a while (and because I have a lot).

During this process I had to eliminate a LOT of almost-duplicate colors, and ones that just didn’t speak to me. Some were easier than others.

It’s OK if you keep two similar colors and do more testing, until you really get a feel for them. Most likely the more you paint with them the more you realize you lean towards one or the other.

Because I’m so familiar with my colors and process it was pretty easy to know which ones I preferred.

However there were some exceptions!

In this case, I did much more testing. It’s VERY important that my colors play nicely with eachother. By that I mean they must be able to mix with other colors and yield clean mixes (not muddy). This is easier when the tube contains a single pigment versus many pigments. For example, Naples Yellow Reddish by Schmincke contains 4 pigments (PW6, PW4, PR242, PY42) and is opaque. I was tempted to keep it because it offers a good base for peachy tones like skin or architectural elements. But when mixed with certain other colors, it creates icky muddy tones. CUT.

I also had to decide between two yellows: lemon yellow or hansa yellow. A lot of artists insist on having a lemon and a warm yellow on their palette because they have subtle differences. I can understand that for certain artists, their subject matter dictates a need for such a minute difference. However for what I do, I never, ever need more than one yellow in any given painting.

Since I have only ever used lemon yellow a handful of times, it was a relatively easy one to cut. However I did give it a fair chance by mixing it with my blues (since green is an important color in my work). But Hansa yellow was the clear winner!

Fill in the Gaps

Finally, with only 14 colors, I had some room to play. As I was doing my research, there were two colors that kept pulling at me. I blame In Liquid Color and Dr Oto Kano (mentioned above) because they mention them so often.

So I went ahead and ordered:

PR122 Quinacridone Magenta

PB60 Anthraquinone Blue (or “Indanthrone Blue)

I am not a huge fan of red, and it rarely finds a place in my paintings. If anything, I go with earthy reds like Indian red or venetian red. But once in a while I find the need for a more vibrant tone. I had kept Sennelier Red as a “just in case” color, but just the thought of using it makes me cringe!

Through watching videos, I started to learn that a nice punchy red can be achieved by mixing Quinacridone Magenta with colors like Quinacridone Burnt Orange (which is on my palette). So I thought, instead of just using an intense red straight out of the tube and trying to tweak it, which is sometimes difficult because of it’s intensity, I want to utilize two colors that allow me more freedom.

As for the blue, I needed a rich, deep blue to replace the Sennelier indigo that I cut out - one of my favorite colors but one which disappointingly contained three pigments, and did not have the best reputation for mixing well with others.

Next Steps

In Part 2, I will show you my new palette, all the color mixes, and other insights that helped me finalize this process! Thanks for joining me on this journey!